The Cartographer of Time: Using Vintage Cameras to Trace Photographic Evolution

There’s a peculiar magic in holding a camera that once belonged to someone else, a tangible link to a different era. It’s more than just holding an object; it’s inheriting a perspective, a history etched into the metal and glass. As someone deeply involved in restoring vintage film cameras, I've found myself increasingly fascinated not just with their mechanics, but with the story they tell about the evolution of photography itself – a narrative best understood by viewing these cameras as points on a chronological map, each representing a milestone in our relentless pursuit of capturing reality.

My first encounter with this realization came from a battered Kodak Brownie Hawkeye. I’d picked it up at a flea market for a few dollars, drawn to its unassuming simplicity. The paint was chipped, the shutter sticky, but something about it resonated. Restoring it wasn’t just about cleaning and lubricating; it was about unlocking a moment, a feeling from a time when photography was a novelty, a shared experience, a relatively expensive and deliberate undertaking. The Brownie democratized photography, putting it into the hands of everyday families. Before that, photography was largely the domain of professionals and the wealthy, requiring complex equipment and lengthy exposure times. The Brownie, with its snapshot simplicity, changed everything.

From Daguerreotypes to the Dawn of Mass Photography

To appreciate the significance of the Brownie, we need to journey back further. The very beginning, the daguerreotype, is almost incomprehensible to modern eyes. Imagine a process requiring fifteen to thirty minutes of exposure time, producing a single, incredibly detailed image on a silvered copper plate! The early photographers were pioneers, artists in their own right, battling the limitations of their technology. The initial years of photography were more akin to painting or drawing; the process demanded skill, patience, and a steady hand. The invention of the collodion process in the 1850s – wet plate photography – dramatically reduced exposure times, but the photographer still needed a portable darkroom to prepare and develop the plates on-site. This truly was a laborious undertaking, a blend of chemistry, artistry, and a spirit of relentless experimentation.

The ambrotype and tintype, born from the wet plate process, offered more affordable alternatives, broadening access slightly, but still remained relatively specialized. The introduction of dry plate photography in the 1870s, with gelatin emulsions, was the next major leap. It eliminated the need for a darkroom in the field, offering photographers greater freedom and portability. Think of the early landscape photographers, venturing into uncharted territories, documenting the American West with their box cameras and portable darkrooms. Their images aren't just photographs; they are historical documents, visual testaments to a rapidly changing world.

The Rise of Roll Film and the Kodak Revolution

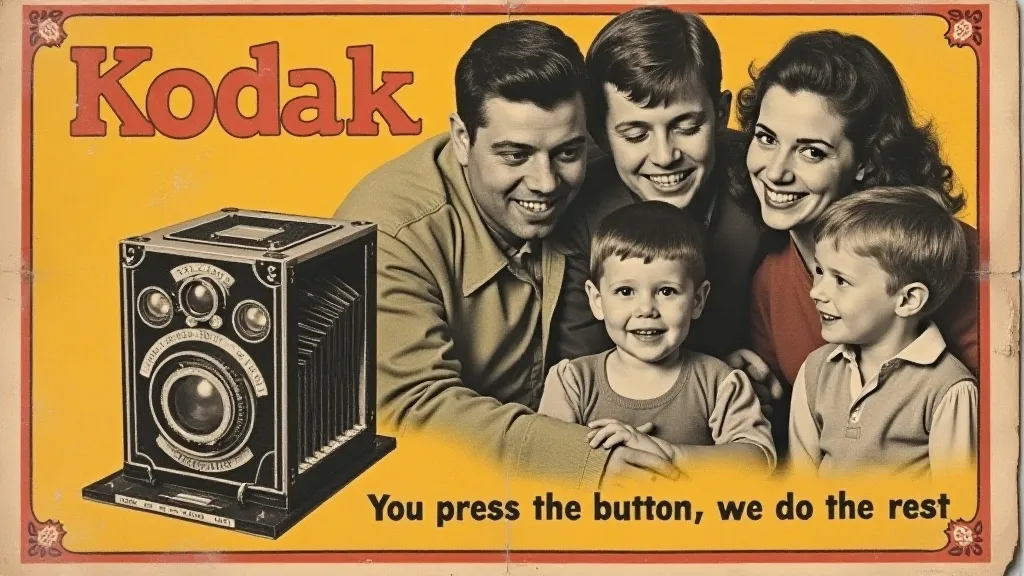

And then came George Eastman and Kodak. The introduction of roll film in 1889 was a watershed moment. Eastman’s genius wasn’t just in the technology itself; it was in the concept of simplification. “You press the button, we do the rest,” the Kodak slogan proclaimed. This encapsulated the vision – to make photography accessible to everyone. The original Kodak camera came pre-loaded with enough film for 100 exposures. After shooting, the entire camera was sent back to Kodak for processing and reloading. It was a revolutionary business model, and it fundamentally altered the landscape of photography.

Following the success of the original Kodak, Eastman continued to innovate. The Brownie, introduced in 1900, was even more affordable and simpler to use. It wasn't about high art; it was about capturing memories, family moments, and the everyday experiences of life. The Brownie ushered in an era of snapshot photography, paving the way for the ubiquitous point-and-shoot cameras of the 1950s and 60s. These cameras, often plastic and brightly colored, represented a shift towards consumerism and instant gratification – a world away from the meticulousness of the daguerreotype era.

The Rise of the SLR and the Pursuit of Precision

As photographic technology matured, so did the demands of photographers. The introduction of the single-lens reflex (SLR) camera in the 1930s marked a significant advancement in precision and control. Suddenly, photographers could see exactly what the lens was seeing, eliminating guesswork and allowing for greater creative freedom. The early SLRs were complex and expensive, but they quickly became the cameras of choice for professionals and serious amateurs.

The subsequent decades witnessed a constant stream of innovations: faster lenses, more accurate metering systems, interchangeable lenses, and more sophisticated film stocks. Cameras like the Nikon F, the Canon AE-1, and the Pentax K1000 became iconic symbols of the photographic golden age. These cameras weren't just tools; they were extensions of the photographer's eye, allowing them to capture the world with unprecedented clarity and artistry. The evolution of SLRs represents a journey from simplicity to sophistication, a testament to human ingenuity and our relentless pursuit of photographic perfection.

Restoring More Than Just Metal and Glass

Restoring these vintage cameras isn’t merely about cleaning and lubricating gears. It’s about reconnecting with the past, understanding the ingenuity of the engineers and designers who created these machines. It’s about appreciating the craftsmanship and the attention to detail that went into their construction. Each camera holds a story, a history, a connection to a time when photography was a more deliberate and meaningful experience. Holding a restored Nikon F, feeling the weight of the metal, and understanding the precision of its mechanics, evokes a profound sense of respect for the legacy of photographic innovation.

More than that, restoration allows a small piece of photographic history to live on. These cameras weren't designed to be disposable. They were built to last, to be cherished. And by bringing them back to life, we’re not just preserving machines; we’re preserving a part of our cultural heritage. When someone picks up a restored Brownie or a Nikon F and takes a picture, they’re not just creating an image; they're participating in a century-long tradition of capturing the world through the lens – a truly remarkable legacy.